Millions of addicted, thousands dead, and social costs reaching up to two percent of the GDP – such is the current impact that illegal drugs have. At the same time, Europeans spend at least 24 billion Euro for them each year. Although at first glance, these statistics may seem to be horrific, in comparison to the United States, where the number of deceased is much greater, this is a good result. This is primarily thanks to a balanced approach between law enforcement and public health, whereby the decriminalisation of use has proven to be an unequivocally effective step. However, although the situation in general is not bad, many blind spots and new challenges remain. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) aims to help countries, and thus it recently published its Strategy for the period until 2025. Thanks to it, it hopes to contribute to a healthier and safer Europe, and not just provide data and analyses, monitor trends, and share best practices. The Centre introduced the strategy at the conference held last autumn that was dedicated to addictions, Lisbon Addictions 2017, which Zdravotnický deník (Healthcare Daily) also participated in.

“For over twenty years in Europe, we have been using a balanced approach between law enforcement and public health. There are, of course, differences from country to country, but not that great. In contrast, the USA has placed an emphasis on law enforcement for many years, often without a similar emphasis on public health,” the Director of the EMCDDA, Alexis Goosdeel, points out.

For instance, the results show that whereas in 1990, 20 to 25 thousand people were undergoing methadone treatment, this number has been increased to the current 650 thousand, and intravenous drug use is decreasing. If we were to look at the number of users, according to the European Drug Report 2017, there are 1.3 million high-risk opioid users in Europe, whereas in the EU, substitution therapy coverage is at about 50 percent. In those states that entered the EU after 2000, however, the availability of substitution therapy is often not as accessible – in Latvia, for instance, it is only 10 percent.

As for illegal drugs in general, the situation is such that in the past year, 1.8 million Europeans used amphetamines, 2.7 million used MDMA, 3.5 million used cocaine, and 23.5 million used cannabis. In the EU Drug Markets Report by the EMCDDA and the Europol, published in 2016, the minimum size of the market was estimated for the first time (which means that it is evidently much larger). According to it, Europeans spend at least 24 billion Euro each year for illegal drugs. “My guess is that this amount is probably closer to 32 billion, maybe even more,” adds Goosdeel. At the same time, approximately 1.4 million people were being treated for illegal drug addiction.

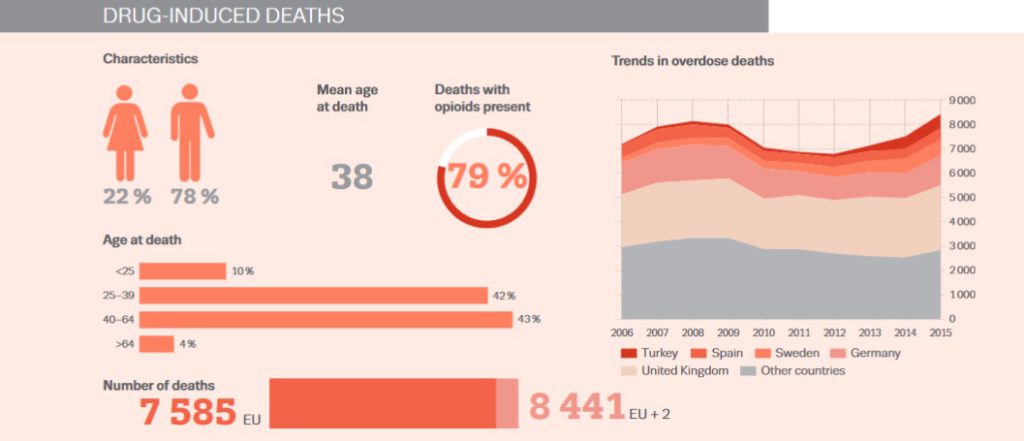

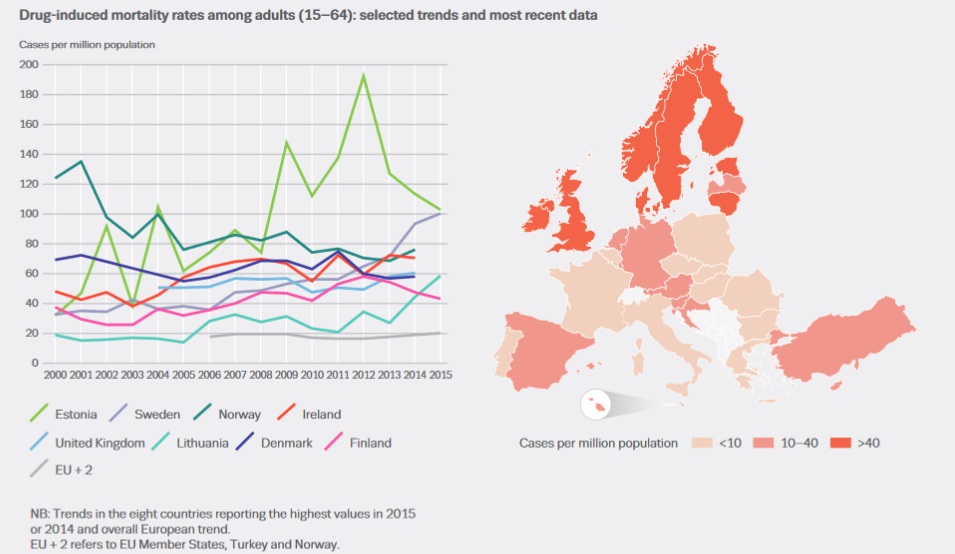

Although this problem involves a large number of people, if we compare the overdose death rate of the EU and the USA, there is an obvious significant difference apparent already at first glance. Whereas in the USA, which has a population of 327 million people, there is an overdose death rate of 160 people per day, in the EU, with a population of 510 million people, there were slightly more than 7,500 deaths in 2015 (i.e. ca. 21 deaths per day). Even the Czech Republic does not need to be ashamed in this area – quite the contrary. In 2015, 44 people died of overdoses, and according to the Institute of Health Information and Statistics, this number has been moving between 20 and 40 deaths since the beginning of the millennium.

How the Czech Republic has dealt with the (de)criminalisation of drug use

What is the cause of these on the whole very positive numbers? Let us take a small excursion into history. In the 1990s, the Czech Republic decided that it would take the path of decriminalising drug use so that addicts should not have to be afraid to seek out help. According to the National Drugs Coordinator, Jindřich Vobořil, we were inspired by Great Britain at the time, where in 1988, Margaret Thatcher’s government came to the conclusion that HIV was a much greater problem than the drug use itself, and so it chose to take steps to reduce risks. Today, a pioneer and oft-cited example in this field is also Portugal, whose current legislation, which anchors the decriminalisation of all drug use from cannabis to heroin, dates to 2000 (for an idea – in Portugal, no one who is in possession of drugs for personal use for the period of less than ten days, i.e. a gram of heroin, ecstasy, or amphetamine, two grams of cocaine, or 25 grams of cannabis, is arrested). The result was a dramatic decrease in HIV infections, overdose deaths, as well as the fact that people did not need to be afraid to seek out help.

Although this approach was at first also promoted in the Czech Republic, the state of things changed under the government lead by the Social Democratic Party. However, the experts warning against such changes remained alert and continued to monitor the situation. Thanks to this, the Impact Analysis Project study carried out between 1999 and 2001 discovered that the approach recommending greater repression does not work as well as its authors would hope. The expected deterrent effect was not created, nor were the promised health benefits for society, yet costs increased – just the added social costs alone reached an amount of at least 61 million. Luckily, policies were successfully changed, and fast enough so that the former policies did not have a chance to adversely effect the spread of diseases among drug addicts or the number of overdose deaths, a rate which remains to be one of the lowest in the world. Today, the problem with illegal drugs in the Czech Republic is relatively small, and organised crime is also practically non-existent here.

Both our own experience, as well as foreign experience shows, however, that a drug-free society, as we had again laid claim to in New York two years ago, is a mere illusion. We should, therefore, focus on harm reduction, and that by implementing financially reasonable measures. “Countries that have a lot of money, like the USA, can find financial resources for doubling the number of prisons – 50 percent of US prisoners are incarcerated due to drug crimes. We do not have so much money. We also speak of an equilibrium between repressions and help,” says Jindřich Vobořil, who adds that here, our prisons are not overflowing due to criminals with petty drug crimes, but still, one out of five prisoners is jailed for drugs – and more public money goes to finance repressive measures than services. In 2016, the public budget provided a total of almost 1.54 billion for this issue, of which over 903 million financed law enforcement.

Our greatest problem is alcohol

On the other hand, the Czech Republic has achieved another success that is not a matter of course among the other EU member states – we are one of the 11 states with an integrated approach that does not only treat illegal drugs, but also tobacco, alcohol, or gambling. Sadly, even though we are fairly successful in terms of maintaining a low amount of infections among drug addicts or in service accessibility (80 percent of addicts utilise at least one of them), we are lacking in the fields of legal drugs, especially alcohol. Whereas the number of deaths caused by illegal drug overdose is low, ethanol overdoses occur, in comparison to other countries, almost ten times more often. This has an impact on the number of less serious crimes and domestic abuse, which, in two-thirds of cases, is usually caused by alcohol. Vobořil therefore hopes that the integrated approach that has been in effect for only several years so far will help counter the problem. At the moment, however, improvements to the situation are difficult and slow.

As was suggested earlier, the refusal to criminalise drug use is not an approach that is promoted – although, according to Jindřich Vobořil, not yet to a sufficient extent – only in the Czech Republic. The Global Commission on Drug Policy, the members of which included seven former presidents, issued a report in 2013 that called for the decriminalisation of drug use, pointing out that the war on drugs only helped spread Hepatitis C.

“Repressive drug policies are ineffective, violate basic human rights, generate violence, and expose individuals and communities to unnecessary risks. The Hepatitis C epidemic, totally preventable and curable, is yet another proof that the drug policy status quo has failed us all miserably,” stated then-Commissioner and former Swiss president, Ruth Dreifuss. “It is time for reform,” the report states.

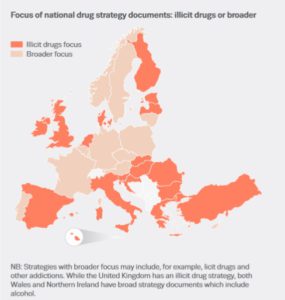

Thus, today, most European countries have decriminalised, either in legislation or in practice, the possession of smaller amounts of drugs. Even though each country still decides on its own drug policies, there is an effort to get advice about best practices also on the European level. “The competences of the EU on drugs are limited. There is an important element present on the European level, however, and that is the coordination and support of policies,” Alexis Goosdeel points out.

The Strategy promises new data and analyses

This is another reason the EMCDDA recently published its new Strategy, in which it determines its role and tasks up until the year 2025. “This is the first time the Centre has a strategic document for the long-term. What is new is the fact that it places emphasis on the clients – the people who are to benefit from our work,” says Alexis Goosdeel.

The Strategy has two main goals: to contribute to a healthier, but also to a safer Europe. It wishes to achieve this in several ways. The EMCDDA understands its role in the development of a better and more complex monitoring, which would show the extent and the trends of drug use, provide relevant data and analyses, identify risks and new risky behaviour in a timely manner, or support intervention methods focused on drug use that have proved to be effective. An overview of the current situation, trends, and effective solutions have been now published as the European guide titled Health and social responses to drug problems. The Centre in it deals with new problems brought on by the new psychoactive drugs, the potential weakness for addictive substances that migrants and asylum seekers might have, or the new manner of drug sales utilising information technologies. It also deals with old problems, such as opioid overdose or Hepatitis C.

The Centre hopes to contribute to greater safety by, for example, a greater focus on attaining data on the drug market or on the nature of drug-related crimes, or eventually by identifying safety risks and by supporting swift reactions.

“Before, we primarily needed information. Today, however, our clients and stakeholders need analyses, not just information. We are surrounded by plenty of information, and therefore it is necessary to know what to think about it. This is one of the main changes, if not the main change, presented by the Strategy,” explains Goosdeel.

As for public health, the EMCDDA now has three priorities: testing and treating drug users (HIV, Hepatitis C), lowering the number of drug-related deaths, and to include best practices in prevention in the prevention programmes promoted by experts in each member state. In connection with the last mentioned action, the EMCDDA has already trained in Slovenia, for example, approximately fifty experts in the field of best practices in prevention. This year, the European Centre should also support the offer of testing and consultations for HIV and Hepatitis C. It wishes to also provide advice for testing, including its translation into various European languages.

It is the availability of information in one’s native language that represents another goal of the EMCDDA. In the future, it hopes to have web pages in various languages that would make at least some of its data, documents, and reviews available, including a simple, comprehensible overview of each substance, its effects, and possible aid. It thus hopes to provide qualified information not only to its stakeholders, but also to the general public.

Michaela Koubová